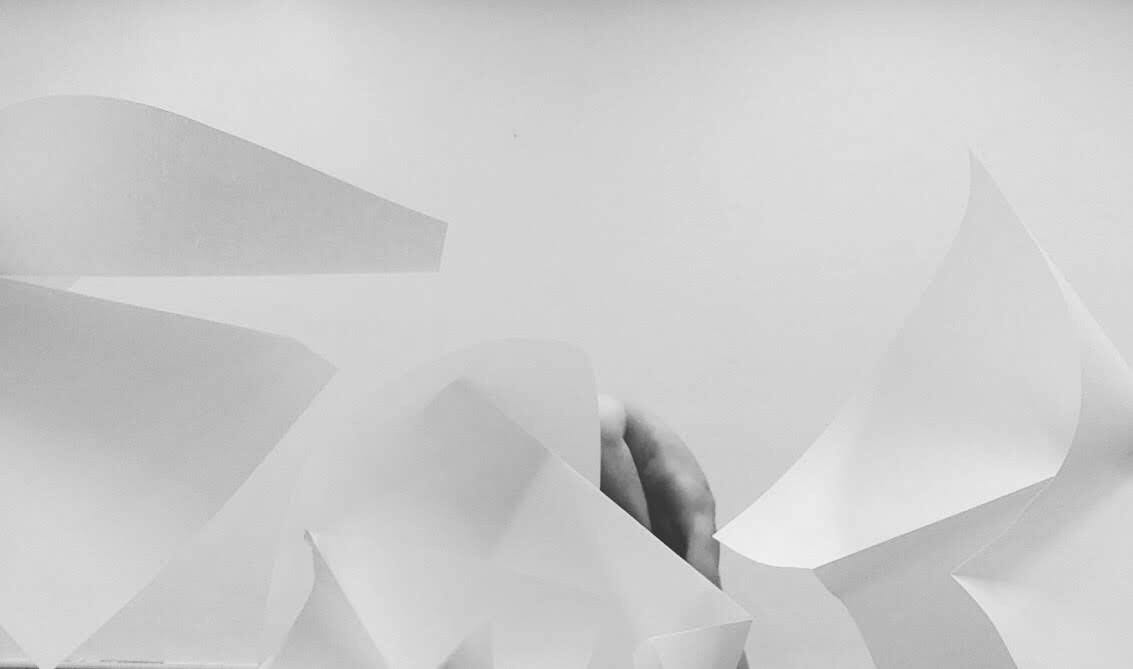

Flesh and Origami by Michael O’Connor

Michael O'Connor discovers that paper folding reveals that human bodies work as archives of evolutionary folds where dancing, writing, and speech cross over each other. Through experiments with nine artists, he shows that the body isn't metaphorically like origami. It is origami.

Two men selling homemade origami on a Vienna street tell Michael O'Connor something that shouldn't make sense: "You don't have to use math. You can feel it." This becomes the key to unlocking a theory about what humans actually are.

Michael's response? Gather nine artists from five countries and spend an afternoon folding paper. Document everything. The observations come fast: "Unfolding is not undoing." Overworked folds don't help. Once you get it to bend it becomes satisfying. The periphery affects the center. Folding leaves marks in material, making it harder for different folds to take place without the entire material becoming affected.

These are evidence for something extraordinary: the human body functions as origami. Not metaphorically. Actually.

The body is a folded meshwork of tissue and nerves, an archive of evolutionary folds where sound, song, writing, dancing, speech all cross over each other, creating surfaces we call human. Nothing gets subtracted when new folds are made—the shape simply reforms, hiding changes inside where they're hard to track. Just like paper.

This logic explodes conventional categories. What actually separates spoken text from song? A sketch from dance? We've made folds to create these distinctions, but poets speak in cadence and people speak in songs. The boundaries are inventions, marks we've creased into being.

Here's where it gets stranger: In origami, a fold between two distant points brings other points closer together. A mountain fold creates sharp angles between neighbors. A valley fold encloses depth. So when dancing emerged as distinct from drawing, what other human capacities were suddenly brought into proximity? What surfaces of experience touched that had been separate? What got hidden inside the fold?

Michael uses paper to think through flesh. Each crease becomes a way of investigating how humans accumulate complexity, how we become certain images constructed from interactions and traces. The body isn't fixed beforehand—it's continuously refolding itself, creating new boundaries while keeping everything that came before.

"If your creases aren't crisp, some structure and possibilities are forfeited," one participant observes during the folding experiments. The same applies to human evolution, to personal development, to every distinction we make between disciplines and ways of knowing.

Michael has found a way to make visible what normally remains hidden: how the body thinks, how boundaries form, how human capacities emerge from a single sheet that never stops folding back on itself.

Read Michael O'Connor's full essay in Issue 04: Structure of a Dance Mag