Continual Becoming: Alina Belyagina on Performativity, Collapse, and Feminist Dramaturgy

From West Siberia to Munich, Alina Belyagina has turned periphery into method. Her new work fuses vogue and Slavic folk dance to explore how bodies migrate between traditions and carry memories that discourse hasn't yet mapped.

What does it mean to work from the margins when the margins themselves are a form of knowledge? For choreographer Alina Belyagina, the periphery isn't a geographic fact—it's an epistemological position and a strategy for staying "critical, inventive, and connected to what's missing."

Her new work, Giving back the Blessings, places two politically charged traditions in conversation: vogue culture born from Black and Latinx queer ballroom resistance, and Slavic folk dance with its freight of gender codes and national identity. Both are competitive, rule-bound, and emerge from communities navigating oppression. When Alina asked Russian colleagues what dance could be protest today, someone replied: "any folk dance, except Russian folk dance."

The pairing raises questions about cultural transmission and survival. What does it mean that the same bodies are drawn to both forms? Alina tracks how movement carries the memory of decolonization, how dancers migrate between traditions that discourse hasn't yet mapped.

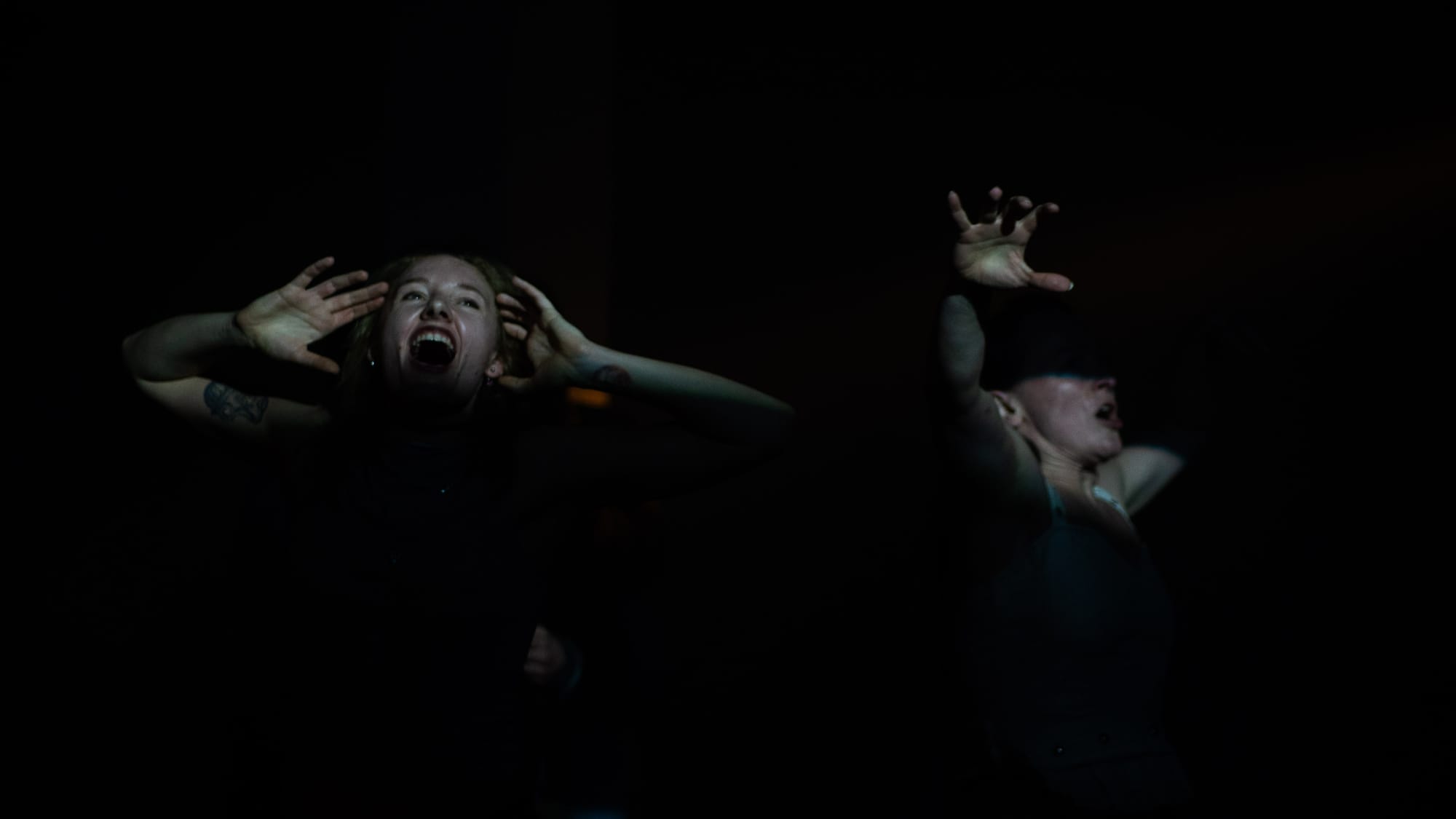

Her feminist dramaturgy rejects climactic structure for fragments and loops. At Munich's Lothringer13 Halle, moving cranes and shifting light operate as co-actors, sometimes more active than the dancers. Sound exists before anyone arrives and continues after they leave. It's an aesthetics of incompletion and refusal—of practices she "sometimes cannot (and don't want to) name."

While waiting for the work third performance at Lothringer13 on November 22nd, 2025, we spoke about epistemologies of the margin, the politics of bodies in motion, and why she keeps her rehearsal windows open to the street.

Your artistic journey has taken you from West Siberia through Kyiv, Moscow, and Katowice, before settling in Munich. You mentioned wanting to discuss your work 'from the perspective of the periphery and province'. I'm curious about that framing itself, why do you think we categorize certain places as peripheral or provincial in the arts world? And what does it mean to claim that position, rather than simply saying you've lived and worked in multiple places?

When I speak about the periphery, I don't mean it only as something geographically distant from the centers of contemporary dance. For me, the periphery is a condition, a space without resources, without infrastructure, sometimes without understanding. And this doesn't apply only to dance; it can also describe the periphery of life itself.

I often say that my biographical landscape is diverse. Growing up in a small West Siberian city, I didn't imagine multiple futures. The world appeared to me in two directions: Moscow or Kyiv -- and the periphery, where I was. Because of family circumstances and financial realities, I didn't have skills to imagine where else I could be. Only when I began to dance, I started to move differently, not just geographically, but also in the way how I experienced life. The multiple dance practices provided me also patterns of how to live life.

"Why Munich?" or "Oh, it's nice that you're here". But "here”, whether Munich, Sochi, or Katowice, always comes with the same task: to convince people to see dance from another perspective. In Berlin or Vienna, every small niche or experimental format has its place in the professional scene. In Munich, I often need to create a context for myself, for instance, by offering open sessions that raise just as much curiosity as confusion.

Maybe my view would be different if I had followed the "central" trajectory, from Moscow to Amsterdam or to Marseille. But Munich is my reality now, and it is a place that still lacks a proper dance house, but as well curators, and an overall infrastructure to support the local scene. For me, claiming the periphery is not a limitation, but a strategy, a way to stay critical, inventive, and connected to what's missing.

"Observing how the movement mutates, how dancers decolonize themselves, how the movement itself migrates, and how this montage happens."

Your new performance Giving back the Blessings brings together Slavic folk dance and vogue, two forms with very different histories of visibility and community. What drew you to place these languages in conversation?

I had been practicing both of them for the past two years and found similarities in movements such as the crawl or duckwalk, virtuous turns or spins, and deep positions. At the same time, I wanted to dedicate a new piece to the important people I met during that period.

What I notice on the internet or TikTok is that often the performers of either the one or the other dance are the same people. I'm not so much referring to state folk dance ensembles, but rather to dancers who used to practice folk dance and are now part of the vogue community, observing how the movement mutates, how dancers decolonize themselves, how the movement itself migrates, and how this montage happens. I'm also deeply fascinated by the extroverted nature of both dances , they are both highly expressive, each with very strict rules, and at the same time, both are strongly competitive.

The premiere is happening at Lothringer13 Halle as part of the SOMA residency, which positions dance "at the edge of visual art". How does working in this context, rather than a traditional theater space, affect your approach?

My previous works have also taken place in spaces that are not exactly theatrical. For example, Hold Me was created in the atrium of GES-2, with a huge window opening onto a grove, using the sunset itself as the main dramaturgy for the light, Lena Perelman from the Gogol Theater in Moscow assisted with the lighting.

I'm always happy to work outside traditional theater spaces, especially in Germany. Non-theatrical spaces have more technical freedom, I can work with fog, or with a safety harness at height. Lothringer13 offers alternative perspectives on the body. But I also must note that in May 2025, many galleries in Munich invited choreographers to create body-based or choreographic works in the frame of Various Others; however, all of them were international artists, none local.

We do not just use the hall of Lothringer13, but it also shapes our performance, agency is given to the audience by not-seeing everything. Performative elements are often given in hideaways and one must decide to look for them or not. The space is large, and together with the audience it generates a specific in-between state, between dance performance and event, between living landscapes and nostalgia for the future.

I'm exploring how to activate the space where the performance happens, how different images can be traced and re-contextualized there. The moving cranes by Christian Schwarz, the mobile stairs, the cables, the pallet jack are all co-actors of the performance. The light and the sound also inhabit the space, sometimes they are more active than the bodies. I allow the sound to exist before anyone arrives, and to stay after the audience has left.

"When I asked my colleagues in Russia on Instagram what kind of dance could be considered protest today, someone replied: any folk dance, except Russian folk dance."

Vogue emerged from Black and Latinx queer ballroom culture as a form of resistance and self-making. Slavic folk dance carries its own cultural codes and gender expectations. How are you navigating the political weight of both traditions in your choreography?

I think what's important here is to pay close attention to where we are now. Vogue has become a vital, even lifesaving space for many minority communities. We can look at who represents the vogue scene in countries with strong patriarchal regimes, for example, in Russia, where LGBTQ+ rights have been completely dismantled, and persecution is widespread. Despite that, vogue balls still take place, quietly, and at great risk.

To my performance, I critically integrate FemVogue that is a practice I have practiced and is also the focus of my friend and movement advisor, Camila Mos. In every FemVogue class, you can hear rather strange definitions of what counts as "feminine", and what judges pay attention to: the chest, the hips, long hair, long nails. Every movement aims to emphasize these "fem" characteristics.

At the same time, when I asked my colleagues in Russia on Instagram what kind of dance could be considered protest today, someone replied: any folk dance, except Russian folk dance. Of course, it's not the same thing to you participate in the "sex siren" category at a ball, or in a competition of Chuvash folk dance. But I see a political dimension in both phenomena. Thus, I strive to create a performance in which these points of view co-exist, and neither becomes the other, a space defined by multiplicity.

You mentioned "rethinking hierarchy" and exploring "feminist dramaturgy through the body." What does a feminist dramaturgy look like in practice - in the studio, in the rehearsal structure, in the performance itself?

We try to build the rehearsal and performance by rejecting climaxes. I was focused on a fragmented and looping structure. I decided to show the work already at a small festival in Austria just a week after our first rehearsal day. Each rehearsal functioned as a micro-performance exploring presence, affect, and relational listening. I asked myself how to document the side effects of the work, fatigue, pleasure, boredom, silence, as part of the dramaturgical material. My proposal was to establish rotating dramaturgical responsibility, where each participant could curate or navigate one rehearsal or a series of tasks.

I am also focusing on the hierarchy of the mediums we use, voice, dance, sound, lighting. This piece was created for Lothringer13, where lighting takes a rather important hierarchical position.

During my one-month residency at Lothringer13, dance and corporeality were also prioritized, or perhaps even more visible to the street. The windows of our rehearsal space faced the street, creating a feeling of a continuous walk. For me, it's an important aspect to be visible also in the process of making a performance work. Performance, in practice, is created collectively, through the interaction of people, things, material processes, devices, and institutions. This process of knowledge and experience cannot be understood as a one-sided act of a subject toward an object.

"Leftist utopian theories find support in this context: they insist on the necessity to radically imagine forms of life where there are no rigid hierarchies between the living and the non-living, the human and the non-human, knowledge and corporeality."

Leftist utopian theories find support in this context: they insist on the necessity to radically imagine forms of life where there are no rigid hierarchies between the living and the non-living, the human and the non-human, knowledge and corporeality. They propose to return visibility to hybrids, to dismantle the modernist "sanitary boundary" between nature and culture, and to recognize collective, plural origins.

Such an approach is especially significant for artistic and performative practices, where what matters is not what the body represents, but how it is embedded in a network of things, sounds, textures, politics, and meanings.

The process of working on the performance itself, for me, is a space for alternative forms of knowledge, about the dance scene, resistance, and life.

Can you walk us through what happens when a "neutral, somatic body" transforms into a "female body" in your work? What triggers that shift, and what does it reveal?

For me, this transformation happens when I see that a performer's body is conditioned by sexuality, empathy, affect, and desire. This makes the body political, as well as our action what we are doing with it. In this sense, the transformation is not about embodying the "female body" but about revealing the social forces that insist on it, and tracing how, in response, a body can escape, misbehave, or re-assemble itself.

In the current context, the epistemological standpoint is inevitably shaped by my experience as a woman and a feminist. In this sense, the performativity of the body is closer to the definition of Judith Butler: according to her, performativity is a continual becoming where the body is constituted through repetition, attachment, and vulnerability. Even within the structure of the project, I am guided by left-utopian theories. Unlike classical utopias, left-wing utopianism acknowledges the incompleteness, instability, and imperfection of utopia, yet insists on the right to imagine and create alternative forms of life more just to be embodied, more caring, and more collective. When receiving grants and funding, I always welcome the idea of sharing resources and later facilitating the project, but never to be its leader. Of course, the artistic part is based on my choices and aesthetic preferences, but one also can say that by this time of a project, I have usually already done more than six months of unpaid preparation.

I sometimes encounter situations where project participants need a leader or a leader-oriented process. This approach is very alien to me. In such cases, it is difficult to speak about the female body or transformation.

"We need more stories, more collective narratives, more joint attempts to describe what it means to care, to gestate a child, and to fight together." (Sophie Lewis, Full Surrogacy Now, Verso, 2019)

You're opening your rehearsal process through Morning Practice Sharing sessions. What does "sharing practice as research" mean to you, and how does it differ from traditional workshop or class formats?

For me, it's an opportunity to be together with my colleagues from the local scene and to share a perspective, to see and experience performance from within, rather than only from the position of a spectator. I've really come to love the practice sharing format that my mentor, choreographer Anna Konjetzky proposed in her Playground where she invites different artists to share their practices.

Throughout my residency here, I decided not to distinguish but intentionally merge the rehearsals with practices that interest me right now, for example, dancing in high heels to noise music, bringing together hardcore and folk dance.

Workshops and non-representational methodologies, that emerged out of this setting, share common goals: the democratization, de-hierarchization, and decolonization of knowledge. They also offer strategies for dealing with impostor syndrome. Through this montage, I share my perspectives on dance practices today, practices that I sometimes cannot (and don't want to) name, and that's exactly what fascinates me.

"The post-apocalyptic is not something that comes after, but something that is always already here—in the gaps, in the forgetting, in the improvisation that happens when the original is no longer accessible or possible."

Your previous work has often engaged with post-apocalyptic imagery and themes of refuge (Hold Me, Hold Me, Hold, Getting Our Wonder Smashed). How does your new piece connect to, or depart from, those concerns?

In my previous works, post-apocalyptic imagery has often appeared as a way to think through collapse, not only ecological or social collapse, but the collapse of meaning, linear dramaturgies, and of the body's fixed identity. For me, the question "what grows on the ruins" is not just a metaphor for the future, but also a way to work with the present, with what is already broken or unstable.

In Giving back the Blessings, I continue to engage with these themes, but from a different angle. Here, the focus is not on catastrophe or loss, but on what persists, what is passed on, what continues to move, even when everything else seems to fall apart. The folk dance and vogue practices I work with are both forms of cultural survival and transmission. They carry histories of displacement, resistance, and community-building. In this sense, the piece is less about refuge and more about inheritance, about how we receive, transform, and give back what we have been given, even in conditions of precarity.

At the same time, I'm still interested in the fragility of these transmissions. What happens when a dance is repeated in a new context, by a new body, under new conditions of visibility or invisibility? What is lost, what is gained, what mutates? The post-apocalyptic is not something that comes after, but something that is always already here, in the gaps, in the forgetting, in the improvisation that happens when the original is no longer accessible or possible.

Follow Alina Belyagina's work here: